Starlight Expedition, October 12, 2025: Rijeka Crnojevića → Obod → Remains of Watermills → Obodska Pećina → Observation Deck over the Hydroelectric Power Plant → First Cyrillic Printing House of the South Slavs

On October 12, 2025, the Starlight team chose a route that reveals Montenegro in three dimensions: history (medieval Obod and printing), water (river source and old mills), and stone (spring cave and karst formations). In this part of the Skadar region, everything is literally built around water: the town grew up around a rare and powerful spring, roads and bridges obeyed the curve of the riverbed, and industry—from watermills to a small hydroelectric power plant—held on to the stream as the engine of life. Rijeka Crnojevića: the “quiet haven” of old Montenegro

Today, Rijeka Crnojevića appears as a quiet coastal street with boats, kafanas, and stone bridge arches. But historically, this place was far more important than it seems: the settlement’s history is linked to Ivan Crnojević, ruler of Zeta (1465–1490), who, fleeing the Ottoman advance, built a fortress and monastery on Obod Hill, moved his capital there, and thus gave impetus to the area’s development.

The town’s symbol is the stone Prince Danilo Bridge (Danilo Bridge / Danilov most). It was built in 1853 by Prince Danilo in memory of his father, Stanko Petrović; the Mostina house still stands nearby on the left bank. The bridge connected Rijeka Crnojevića with Obod and was part of the old caravan route towards Virpazar.

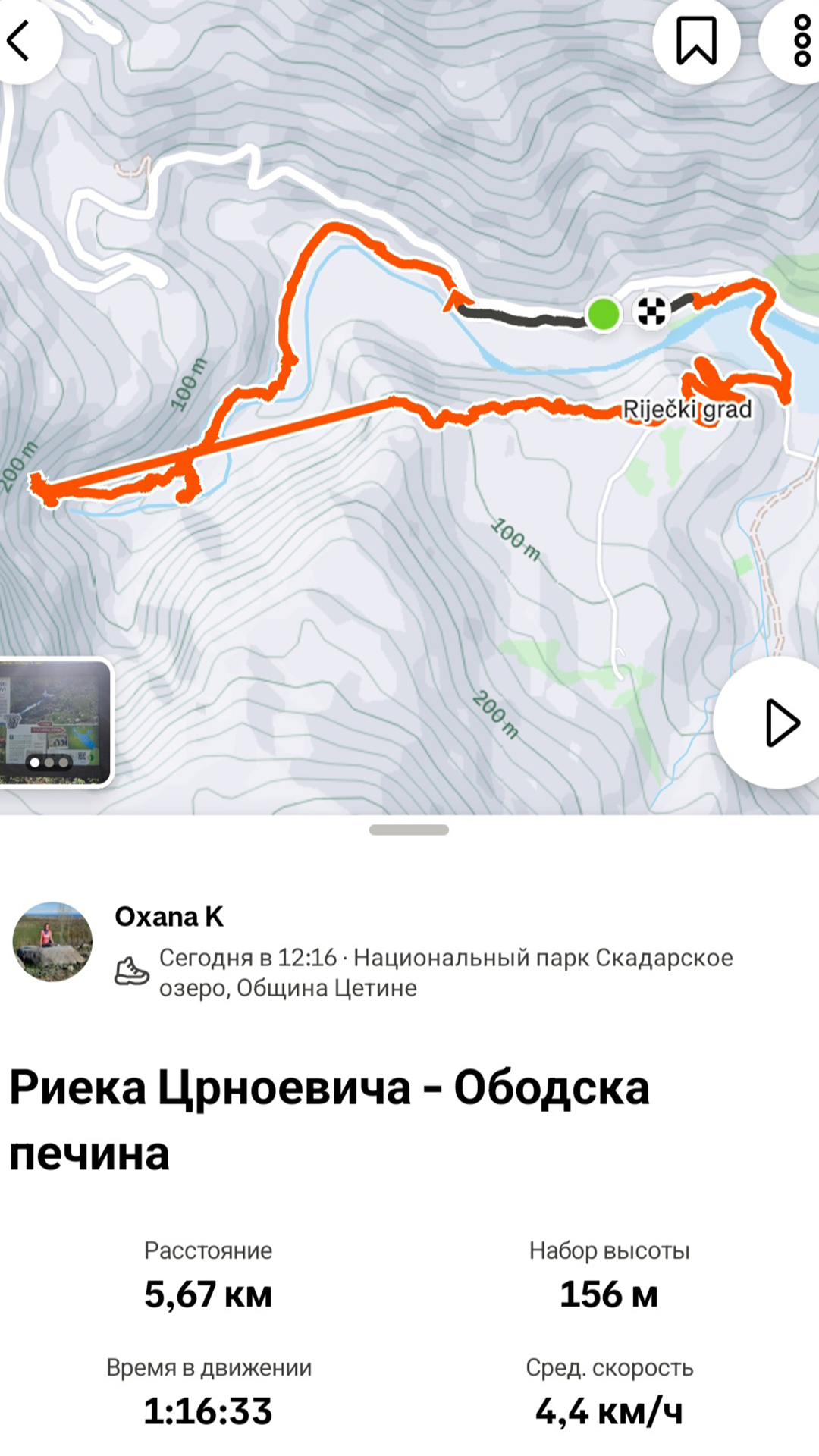

Starlight’s Route of the Day: How Four Points Connected to Create a Single Story

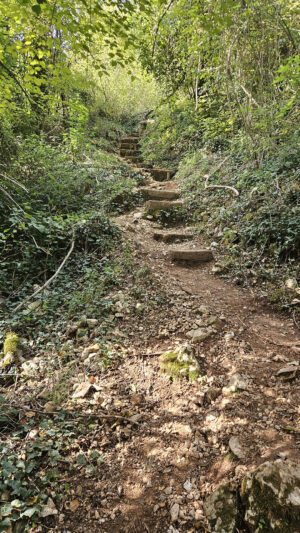

The most beautiful thing about this hike is that the points aren’t scattered, but rather connected by a single logic: the Obod Eco-Trail is a circular, marked route of approximately 8 km that begins at the stone bridge and leads through an old power plant, the remains of stone watermills, to the entrance to Obodska Pećina, and then ascends to the lookout points and the historic Obod Castle.

The Mills of Obod: Water Mills as “Bread Infrastructure”

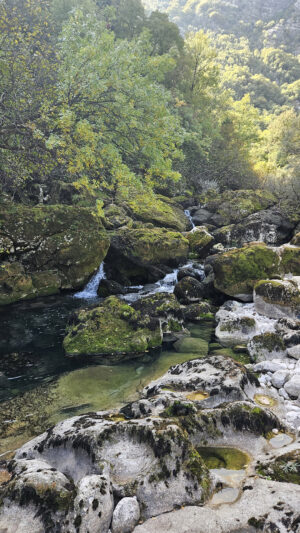

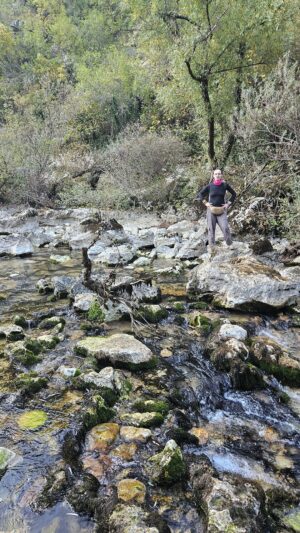

In the sections of the trail where Starlight walked along the water, the former economy is clearly visible: a line of old watermills (Riječki mlinovi) stretches along the riverbed and side channels. Grain was once ground here, and it was the constant flow that made these mills more stable than the seasonal mills on the drying streams. The trail descriptions emphasize that the path literally “clings” to these ruins: water still flows through old stone chambers and channels.

What to see near the mill (if you walk carefully):

- stone walls and “pockets”—places where the mechanisms and millstones stood;

- water conduits/chutes (sometimes dilapidated)—the engineering part of the mill, without which the “architecture” would not function;

- branching points: the mill almost always “asks” for water in a straight line, so the channel is in places deliberately straightened or “framed” with stone.

The mills are also important here as a transitional step to the cave: from “manual” technology (mill wheel/stone complex), the route gradually leads to an “underground water factory,” where the river is born from stone. Viewpoint + Hydroelectric Plant: An Industry That Grew from a Trail

Viewpoint (Vidikovac/Babino): Panoramic View of the River, Road, and Hydroelectric Power Plant

On the way up to the Starlight viewpoint, the “key shot” of the route opened up: below, the Rijeka Crnojevića River, the road toward Cetinje, and the section where the Rijeka Crnojevića small hydroelectric power plant is located. The guidebooks note that from Vidikovac, you can also see the valley above the power plant—that’s where the river’s source and the Obodska Cave are located (the cave itself may not be visible due to the terrain).

Rijeka Crnojevića Small Hydroelectric Power Plant: What’s Historical About It?

The plant itself is part of the country’s “energy biography.” One of the routes explicitly states that the old power plant on the trail was built by the Italians at the beginning of World War II and is considered one of the first in Montenegro.

It’s also important to note that the facility is still operational: according to EPCG, two small hydroelectric power plants (“Podgor” and “Rijeka Crnojevića”) have been reconnected to the grid after complete reconstruction. The reconstruction cost approximately 1.6 million euros. The plants are considered some of the company’s oldest production facilities, and the first kilowatt-hours, according to their data, were supplied to the system back in 1941. It also states that they had been out of operation since 2015, prior to the reconstruction, while “Rijeka Crnojevića” has an installed capacity of 451 kW and a planned output of 1.7 GWh per year.

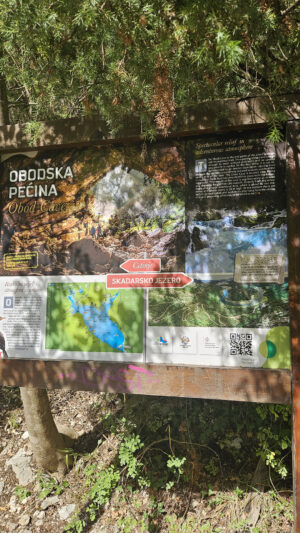

Obodska Pećina: a detailed look at the route’s main “underground stage”

Obodska Pećina (Obod Cave) isn’t a “cave for stalactites.” It’s a spring cave, where water literally organizes space, climate, and danger. For Starlight, it was the highlight of the day: after bridges, ruins, and panoramas—an encounter with what’s usually hidden beneath the surface.

1) Where is it and why do people come here?

The cave is located at the source (resurrection) of the Rijeka Crnojevića River and is visited along the Obod eco-trail; the “resurrection” of water from the depths is considered the main spectacle.

Some descriptions emphasize that the entrance is very large: a “giant portal,” which you reach after about an hour and a half of walking from the start of the circular trail.

2) Entrance and the first few meters: “You can go in,” but it’s a trap.

Cautions

One of the most insidious properties of Obodska Pećina is its deceptive accessibility. According to descriptions, the entrance is large enough to enter without problems, and for the first 100 meters or so, no special equipment is required. Beyond that, however, the risk increases sharply due to the darkness, reduced visibility, and the proximity of a strong underground stream (it can be heard).

The trail guide specifically warns: you can go quite deep inside “to the source,” but you can also get lost, so don’t go without a guide, a decent flashlight (and spare batteries), and without warning those remaining outside.

3) Geology and “Form” of the Cave: What’s Really Inside

The most valuable thing is that Obodska Pećina is well described in scientific literature, allowing us to speak specifically rather than in general terms:

- The cave is formed in layered limestone; The “horns” of the layers are visible on the vault, and the walls and bottom of the upper channels are polished in places by the flow.

- It lies on 3-5 morphological levels and represents a system where water has “reshaped” its path several times.

- The total length of the passages is over 350 meters, and the system is divided into three compartments connected by two siphons.

- The lower channel is only partially passable, meaning the cave naturally “limits” a typical pedestrian visit.

- The altitude “amplitude” is impressive: the entrance is approximately 375 meters above sea level, and the lowest point of the system reaches approximately 244 meters, which gives a drop of approximately 192 meters relative to the entrance.

Translated into human language, Obodska Pećina is not a “hall + corridor,” but an underground hydraulic system with levels, overflows, and sections where the water completely blocks the route.

4) Water as a Director: How the Cave Changes with the Seasons

At Obodska Pećina, the “character” is determined by the flow rate of the spring:

- Obod Spring has a very variable flow rate: from 0.24 m³/s to 46 m³/s.

- Typical minimum water levels occur in November–December, and maximum levels occur in March–April (sometimes February), which is attributed to a combination of precipitation, snowmelt, and temperature.

This directly explains why tourists’ impressions can be “as if they were in different places.” During the dry season, the cave can feel like a lake and the water is relatively still, while after heavy rains, the cave transforms into a powerful water corridor.

There is also a visual description of this dynamic: during the dry season, the main gallery can end in a lake, and after heavy rains, it can become a muddy river, while the entrance often remains relatively dry.

5) Microclimate: Why is the air inside always “different”?

The scientific description emphasizes that constant water creates a humid microclimate.

Sensory perception manifests itself as follows:

- at the entrance, you literally feel a “cold breath”;

- the stone quickly becomes slippery (especially where there is moss/biofilm);

- the sound of water acts as a navigational “beacon,” but at the same time lulls vigilance: it seems that the source is “somewhere nearby,” although the path may lead into side cavities.

One personal account of a visit directly notes that at the entrance, the stones were covered in moss, and one had to tread very carefully due to the slipperiness.

6) Siphons and the “boundary of adventure”

Two siphons are the key to understanding why the cave is simultaneously accessible and dangerous.

A siphon is a section where the passage is filled with water up to the ceiling. For the average tourist, this is a stopover point, but for speleologists, it’s a special training zone (and often a separate permit/safety regime).

Important: even if you don’t plan to go “deep,” strong water and dark forks mean a guide and discipline are more important than “courage.”

7) A Living Cave: Who Lives Here (and Why It Matters)

Obodska Pećina isn’t an empty “stone chimney.” It’s known as a site of biological discoveries: for example, it was here that research was conducted describing freshwater microfauna new to science (as part of research on Gastrotricha), and the cave itself is described as deep, with a river running through it.

More broadly, the groundwater of the Lake Skadar basin is characterized by a high proportion of stygobionts (species living only in groundwater), and several reviews emphasize that the highest numbers were recorded specifically for Obodska pećina.

For visitors, this means a simple thing:

do not touch the water and bottom sediments, do not “wash your hands” in underground puddles, and do not throw away organic matter—the ecology in such systems is very fragile.

8) Safe Visiting Practices (for the “Starlight” route)

If your goal is to repeat the “beautiful part” (entrance + first tens of meters), then the rule is as follows:

Minimum:

- headlamp + spare light,

- non-slip shoes,

- caution on wet rocks (moss is a real danger).

Don’t:

- go beyond the “first zone” without a guide and without understanding where you will end up when the water level changes; Guidebooks explicitly warn of the risk of getting lost.

An important seasonal consideration:

Autumn (including October) is often comfortable for the trail, but it is during transition periods that sudden changes in water levels after rains are possible—the cave “reacts” quickly to water. The best seasons for climbing/hiking routes, according to local descriptions, are early spring, autumn, and winter, in good weather.

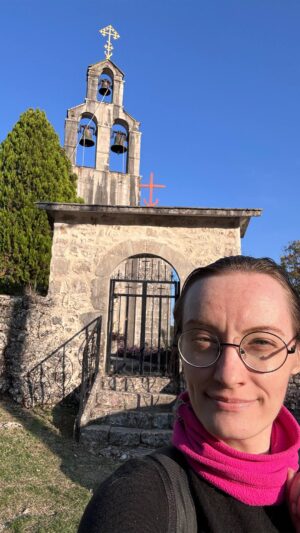

Ob od: when a “landscape” becomes a page of history

After the cave, the route logically concludes with Obod: here, in essence, lies the “top floor” of the entire history of the place. Official materials recall that the Obod area is associated with the tradition of the Obod Printing House and the printing of the first Cyrillic book, Oktoih Prvoglasnik (1494).

And descriptions of the Obod town itself emphasize that the fortification and monastery of St. Nicholas are associated with the period around 1475, when Obod was a political center.

The First Printing House in the Region: Obod (Cetinje) Printing House of the Crnojevići

To complete the article about the Starlight route, it’s important to add another “core” of this region: the birthplace of the first Cyrillic printing house of the Southern Slavs (and one of the first in Southeastern Europe) – the Crnojević dynasty printing house, often called Obod (after the location of Obod/Riječki grad) or Cetinje (after Cetinje).

Why was the printing house established here?

The late 15th century in Zeta/Montenegro was a time of pressure from the Ottoman Empire and, at the same time, a struggle to preserve religious and cultural identity. Against this backdrop, the rulers of the Crnojevići dynasty made a technological breakthrough for their time: they launched the printing of liturgical books to more quickly and accurately distribute texts that had previously been copied by hand.

Where was it: Obod or Cetinje

Both versions appear in sources, and that’s understandable:

- General references describe the printing house as operating in Cetinje (hence it’s called the “Cetinje Printing House / Crnojević Printing House”).

- In the local memory (Rijeka Crnojevića/Obod), it appears as the Obod Printing House, founded in 1493. The site now displays the remains of the foundation and a commemorative plaque with an inscription commemorating the beginning of printing in 1493 and the completion of the first book on January 4, 1494.

The simplest way to put it is this: they are one and the same dynastic printing house of the Crnojevićs, associated with the Obod–Rijeka–Cetinje “belt”; the different names reflect different descriptive traditions.

Who founded it and who printed it

The printing house was founded by the ruler Đurađ (Đurađ) Crnojević and operated for a short time—approximately 1493–1496. Hieromonk Makarije (Makarije) oversaw the printing operation, supported by a team of assistants.

A presentation from the National Library of Montenegro describes it as the first “state” printing house and the second Cyrillic printing house in Europe (this is precisely the source’s wording).

The first book and why it is considered historic

The key date for the Obod route is January 4, 1494: the completion of the book “Oktoih prvoglasnik” (Octoechos of the First Tone). It is often called the first South Slavic Cyrillic printed book (and the first Cyrillic publication in the region of Southeastern Europe).

What the printing looked like: The Octoechos is known for its high-quality typesetting and for being printed in two colors—black and red—and for the design, which included headpieces and initials (a typical “luxury” for incunabula, but executed with great confidence).

What else was printed

According to the National Library of Montenegro, the Octoechos was followed by four more liturgical books:

- Oktoih petoglasnik,

- Psaltir s posljedovanjem,

- Molitvenik (Trebnik),

- Četvorojevanđelje.

The local historical essay Rijeka Crnojevića provides the same typesetting (with the same titles) and specifies that the printing house ceased operations around 1496 amid war and the departure of key participants.

What remains today and how it is “read” on the Starlight route

People now go to Obod (Riječki Grad) not only for the views and ruins of the fortress: an important “point of meaning” is the site of the printing house. There, they usually show:

- fragments of the foundation,

- a memorial plaque commemorating the founding of the Obod Printing House and the date of completion of the Octoechos.

The final impression of the Starlight

This route is rare in that it is not “about a single landmark.” Everything here is causally connected:

- bridges record the history of trade and statehood,

- mills show the “everyday economy of water,”

- hydroelectric power station—an industrial continuation of the same logic,

- Obodska Pećina—a primary source showing how water physically creates a place.